Effect of Recent Pathogen Experience on Induced Sanitary Broodcare in ant L. neglectus

A research internship with Prof. Sylvia Cremer and Linda Sartoris at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA)

Read the full project report here

Social insects – ants, bees, wasps and termites – live in colonies with high densities and have frequent social contact with close relatives who have high genetic relatedness. These factors make social insects susceptible to the spread of parasitic infections, and it is a wonder that they have been evolutionarily successful despite this threat. To counter this risk, they have evolved a suite of colony-level anti-parasite defences to avoid infection and prevent its spread in the colony. This colony-level anti-parasitic defence, called Social Immunity, is achieved by the cooperation of all individuals in the colony across social insects. It is characterised by hygienic behaviour (e.g., grooming each other), physiological defence (e.g., encapsulating the parasite in a barrier of propolis) and spatial organisation (e.g., social isolation of infected individuals).

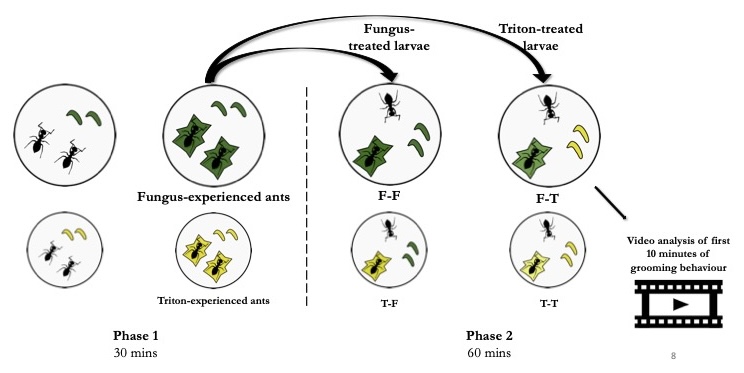

Ants also regulate their behaviour based on past pathogen experience. Ants that have encountered pathogen spend less time in the brood chamber and becomore more efficient at grooming contaminated individuals. In a recent experiment by Linda Sartoris (PhD student in the Cremer Lab), she found that ants that have had a recent pathogen exposure (for 30 mins in Phase 1) – when transferred to an arena with larvae and a naive nestmate in Phase 2 – tend to significantly reduce grooming the larvae as compared to an ant that had been exposed to a control compound in Phase 1. qPCR of the exposed ants showed that they had picked up a small contamination from their exposure. In the context of this experiment, I tried to answer the following two questions.

Are pathogen-experienced ants better at caring for contaminated larvae? - Not really.

Based on the previous experiment, I hypothesized that ants that have had a recent pathogen exposure might be ‘primed’ to care for other infected larvae. I predicted that pathogen-exprienced ants would increase their grooming of contaminated larvae as compared to control-ants exposed to contaminated larvae in Phase 2. To test this, we had 4 conditions based on the treatment condition in Phase 1 and 2 as shown in the image below.

I then manually annotated the timestamps at which the exprienced and naive ant groomed the larvae or each other in Phase 2. I compared the frequency and duration of grooming across the four conditions – pathogen experienced ant grooming contaminated or controlled larvae; and similarly, control (larvae coated Triton-X, a suspension solution for fungal spores) experienced ant grooming contaminated or controlled larvae.

We find that There is no significant difference in the induced brood care of pathogen-experienced or control-experienced ants. This is possibly because Triton-X is an foreign, toxic compound that elicits similar grooming response from ants, and this could be increasing brood care in control treatment. It is also possible that the experimental set up wasn’t good enough to mimic the ants’ natural social enviroment.

Are larvae susceptible to low-level pathogen contamination? - Big time!

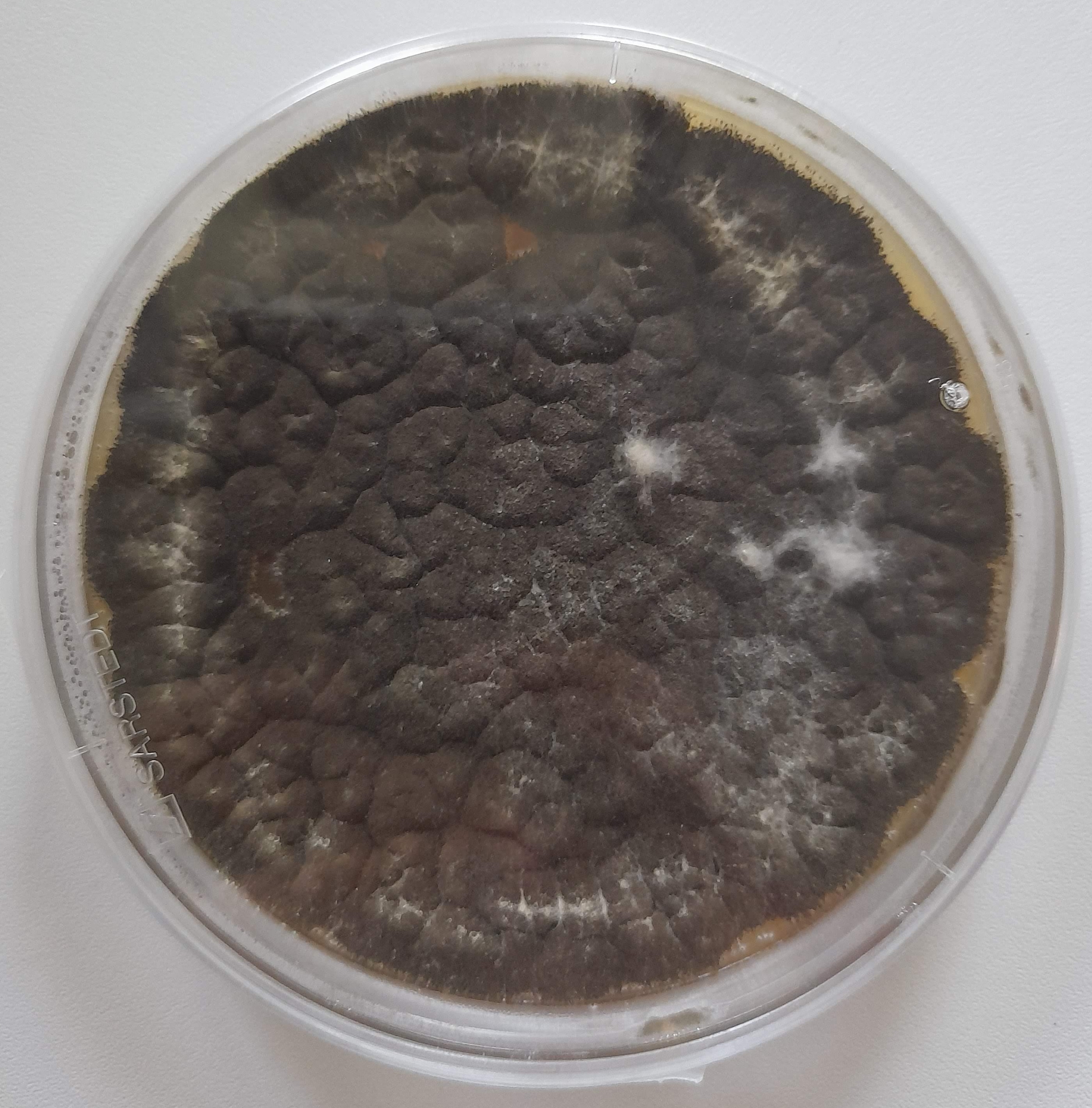

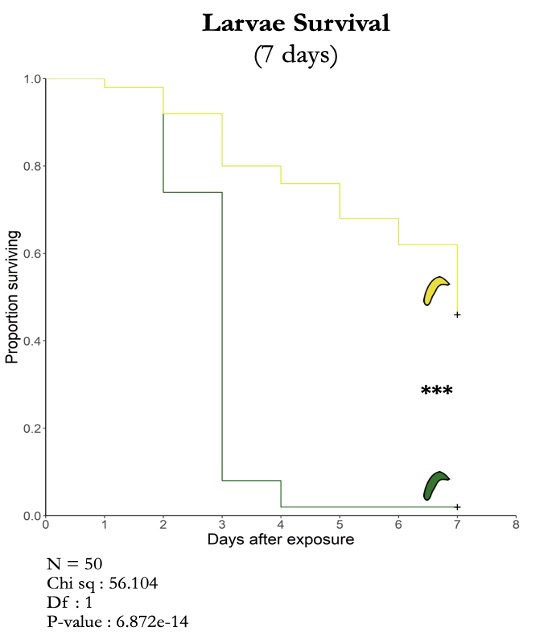

The other hypothesis based on the previous experiment was that – perhaps the pathogen-experienced ants are avoiding the larvae so as to not transfer a low-level contamination to them. This would imply that larvae are susceptible to a low-level contamination. In order to test this, I did a low-level contamination survival experiment, treating 50 ants and 50 larvae to a low level contamination, similar numbers to a control treatment and isolating them for 7 days. I then kept track of the surviving number of ants and larvae throughout the week.

And turns out, isolated larvae are extremely susceptible, even to a low level contamination - most of them die on the third day. In contrast, the control-treated larvae decrease mobility, but they survive longer. Ants show similar survival across treatments, because when ants are contaminated, they can clean the spores off of themselves.

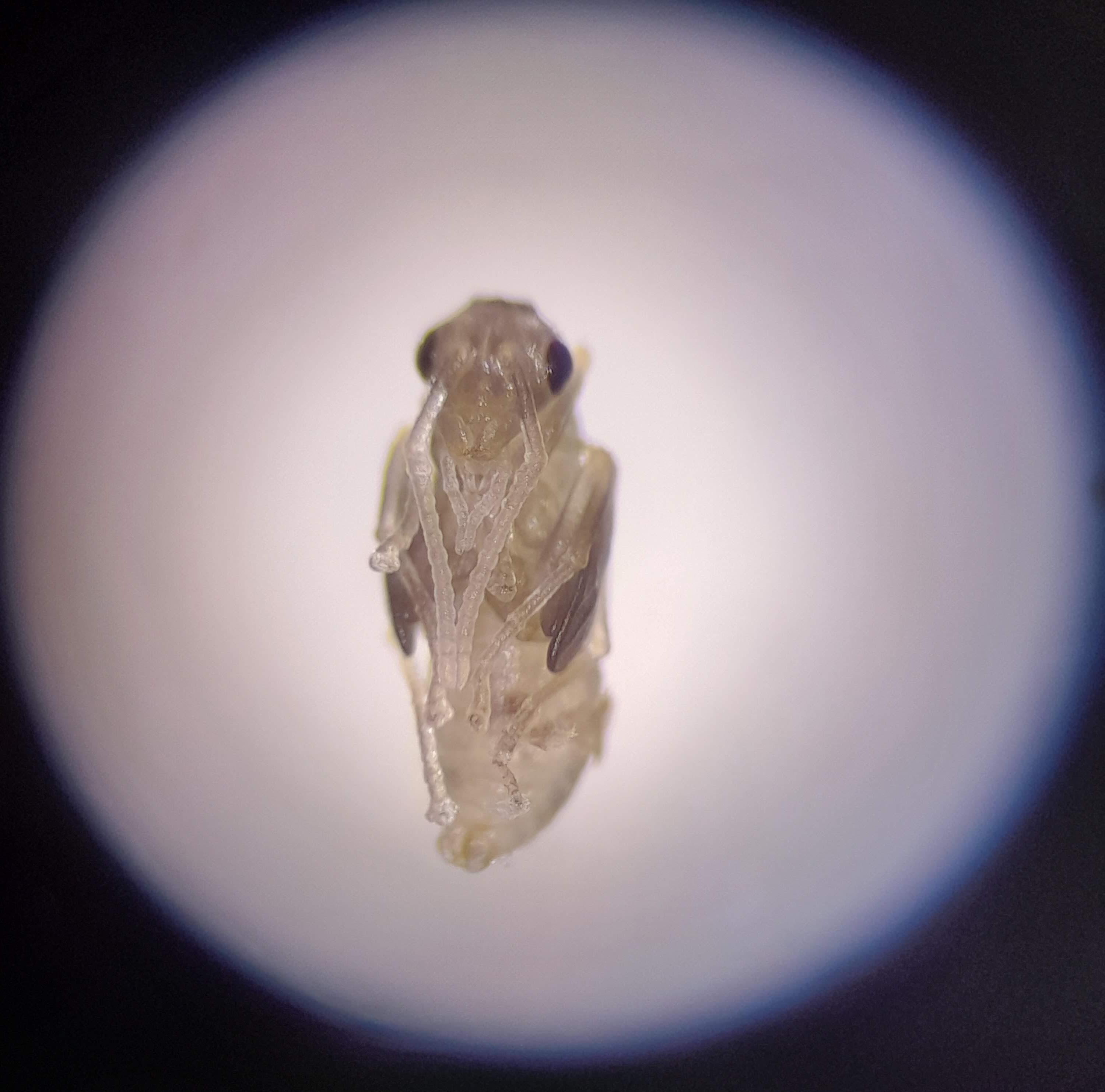

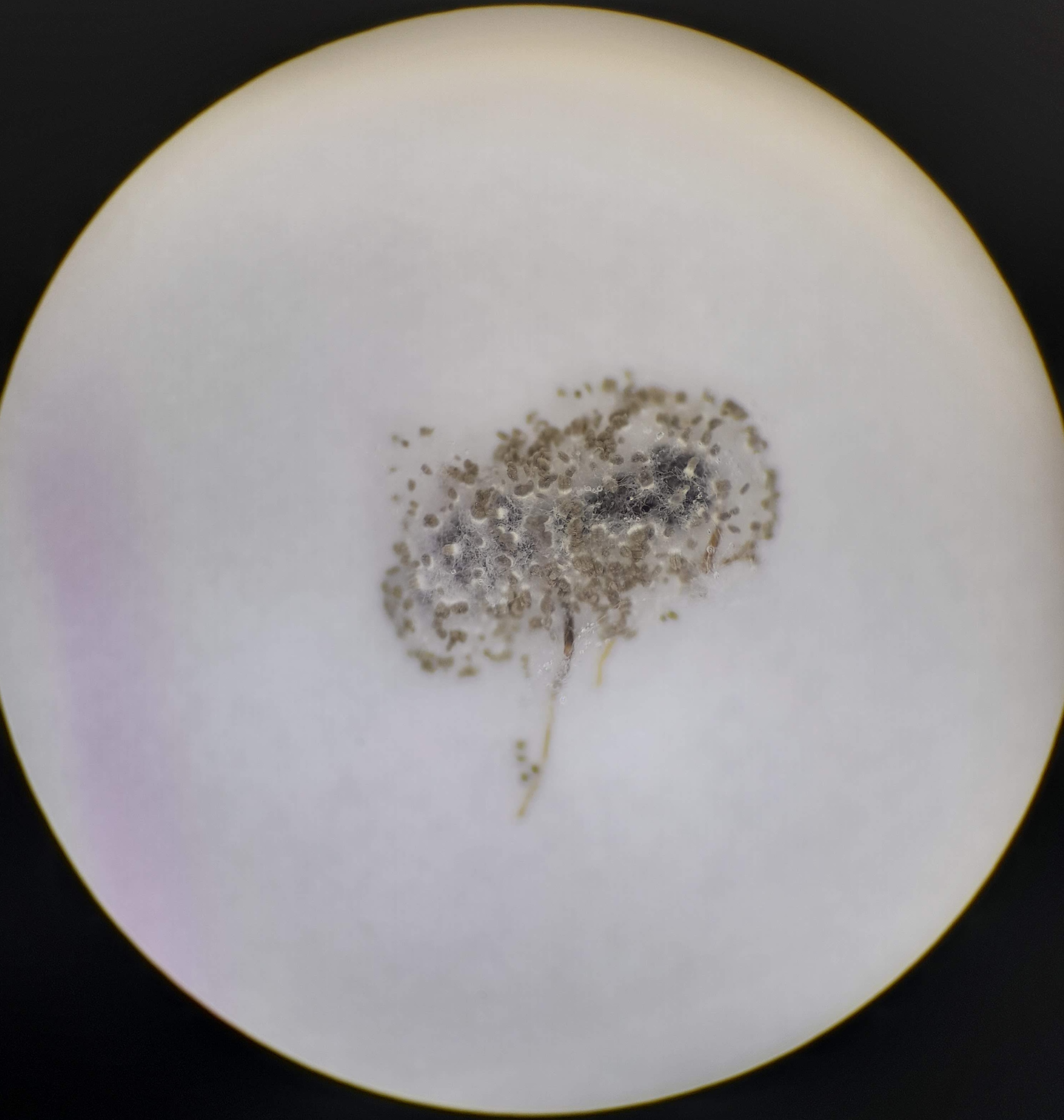

Some interesting pictures from the lab

Acknowledgements

I’m very grateful to Linda Sartoris for being a great mentor, showing me the ropes in the lab, finishing the qPCR of Induced grooming Experiment samples, and sharing her resources of illustrations and statistical analyses. I would like to thank Prof Sylvia Cremer for giving me the opportunity to work with her group at ISTA, and all the Cremer Group members for being helpful, supportive and a lot of fun to work with! I’m also grateful to my fellow summer interns and PhD students at ISTA, without whom this summer wouldn’t have been the same. I would also like to thank Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar, whose article on how insect societies deal with infectious diseases led me to explore social immunity literature and to this internship with Prof Cremer. I acknowledge the support from IISER Pune, Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), and the KVPY scholarship program, which allowed me to pursue this internship.

Further reading

- Cremer, Sylvia, Sophie A. O. Armitage, and Paul Schmid-Hempel. 2007. “Social Immunity.” Current Biology 17 (16): R693–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008.

- Cremer, Sylvia, and Michael Sixt. 2009. “Analogies in the Evolution of Individual and Social Immunity.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364 (1513): 129–42. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0166.

- Reber, A., J. Purcell, S. D. Buechel, P. Buri, and M. Chapuisat. 2011. “The Expression and Impact of Antifungal Grooming in Ants.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 24 (5): 954–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02230.x.

- Tragust, Simon, Barbara Mitteregger, Vanessa Barone, Matthias Konrad, Line V. Ugelvig, and Sylvia Cremer. 2013. “Ants Disinfect Fungus-Exposed Brood by Oral Uptake and Spread of Their Poison.” Current Biology 23 (1): 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.034.

- Ugelvig, Line V., and Sylvia Cremer. 2007. “Social Prophylaxis: Group Interaction Promotes Collective Immunity in Ant Colonies.” Current Biology 17 (22): 1967–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.029.

- Westhus, Claudia, Line V. Ugelvig, Edouard Tourdot, Jürgen Heinze, Claudie Doums, and Sylvia Cremer. 2014. “Increased Grooming after Repeated Brood Care Provides Sanitary Benefits in a Clonal Ant.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 68 (10): 1701–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-014-1778-8.