Reinforcement-induced Reduction in the Number of Introductory Notes (INs) in Zebra Finches

A semester research project with Dr. Raghav Rajan at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune

Read the full project report here

Zebra finches are small birds endemic to drier parts of Australia, living in social flocks of hundred or more individuals. These birds have pronounced sexual differences – the male can be identified by its orange cheek patch, and its song. The males sing a song to attract the female. This song is stereotypical, learnt from the tutor, and once learnt stays the same throughout the life of the male. Zebra finches have been used as a model organism to study the development and mechanism of vocal learning for this very feature.

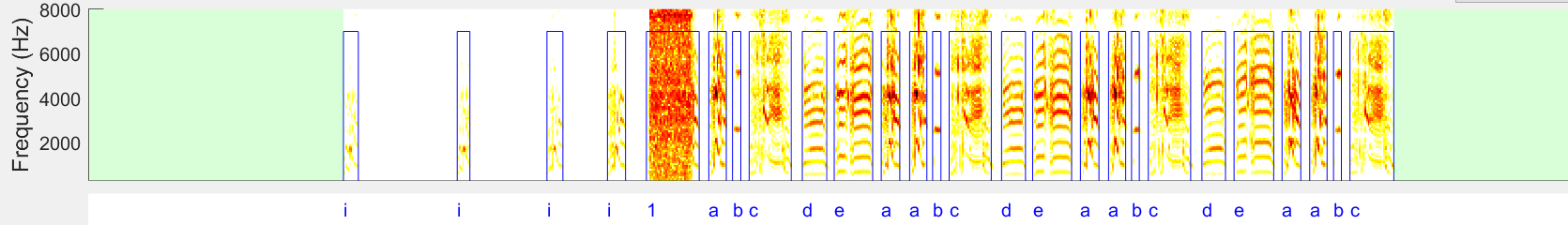

![Spectrogram of Zebra finch song, with INs [i] and motif syllables [a-e]](/images/projects/proj_finch5.jpg)

The song is considered as a complex motor pattern and consists of a particular motif of 4-5 syllables that is repeated across time. The song always begins with short, repeated vocalisations called introductory notes (INs). INs are thought to have a motor preparatory function for when the brain ‘prepares’ parameters to generate the complex movement. A good example of motor preparation is when an athlete dribbles the ball before she throws it into the basket, which improves the accuracy of the throw. The motor preparation hypothesis posits that it helps the brain arrive at a common spatiotemporal pattern of neural activity before the core action is carried out. The motor preparatory hypothesis is supported by the observations that initial, more variable INs converge acoustically to a stereotypical last IN, which signals the readiness of song sequence generation. Additionally, IN-related activity in the brain progresses to a common endpoint just before the song.

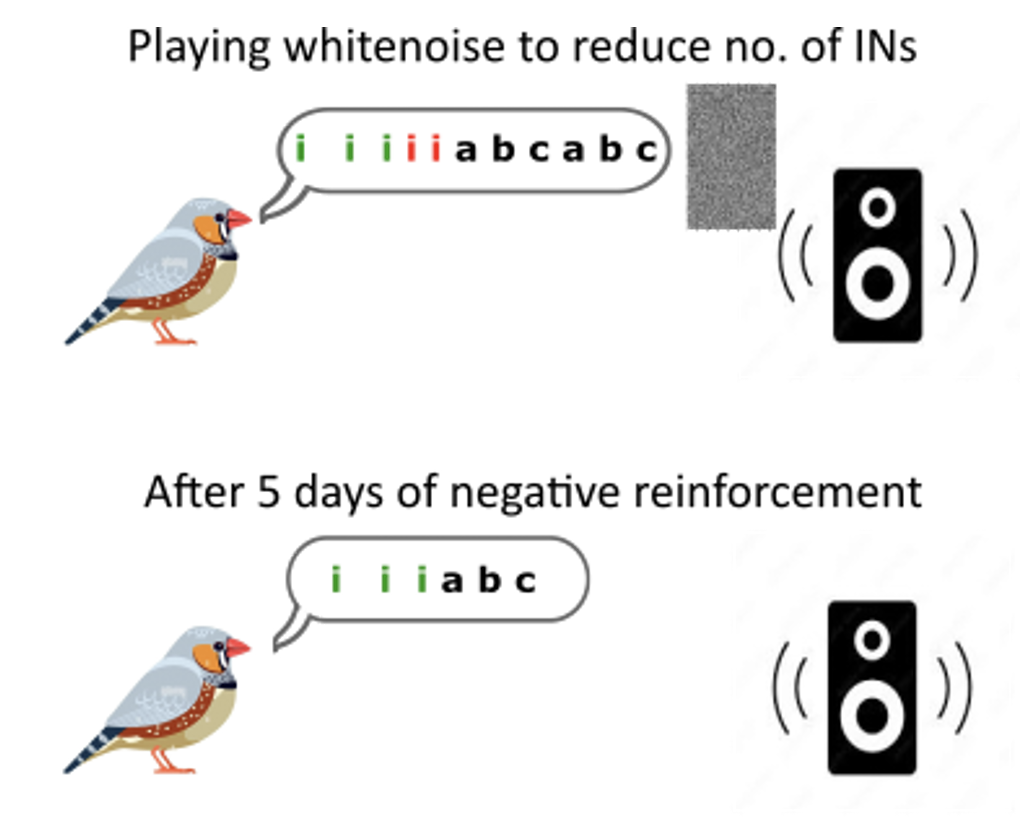

While the song motif is stereotypical, the number of INs varies from bird to bird. Previous studies have shown that IN features, such as, average number and spectral composition, are shaped by both learning and biological predispositions. Other studies have also shown that the song can be modified through negative reinforcement – zebra finches can increase or decrease the pitch of a particular syllable, and Bengalese finches can modify the song sequence when punished with white noise for a particular syllable transition. In this context, the aim of the project was to test whether it was possible for an adult zebra finch to decrease the number of INs by punishing it with a burst of white noise when it sang too many INs.

While the song motif is stereotypical, the number of INs varies from bird to bird. Previous studies have shown that IN features, such as, average number and spectral composition, are shaped by both learning and biological predispositions. Other studies have also shown that the song can be modified through negative reinforcement – zebra finches can increase or decrease the pitch of a particular syllable, and Bengalese finches can modify the song sequence when punished with white noise for a particular syllable transition. In this context, the aim of the project was to test whether it was possible for an adult zebra finch to decrease the number of INs by punishing it with a burst of white noise when it sang too many INs.

The Experiment

Previous studies have used computationally expensive and/or proprietary software and hardware to identify specific syllables and punish them in real-time. In this project, we wanted to use a simpler method to detect INs, like variance of audio data. As a pilot study, the project and experiment were conducted on one adult male zebra finch – Ylw97Ylw29 - that had a relatively high number of mean INs.

Variance is a statistical measure and variance of chunks of incoming audio can be quickly calculated in real time. I first recorded the songs of my bird of interest, and labelled and analysed its syllables. I then compared the variance range of different syllables and determined a certain range where most INs fall. In addition to this, I added two other conditions - a threshold for syllable duration, and the position of the syllable (always at the beginning of the song).

I combined these features into a Python code that would act as IN-detector and added it to an existing Python-based audio recording software developed by Dr Rajan. This modified software would record the bird, and when the bird sang more than 3 INs, it would get punished with a short burst of white noise. I placed the Ylw97Ylw29 bird in this experimental assay with negative reinforcement for 5 days, and compared the mean number of INs in its song before and after these 5 days (10-12 hours each). You can listen to an audio clip of the bird’s song along with a short burst of white noise in the beginning.

It Works!

My modified IN-detector had poor accuracy, resulting from a high number of false positives – that is, the detector thought that some noise and some calls were INs and punished the bird. But the detector had high sensitivity, that is, most songs has white noise played after INs. Despite the poor accuracy, there was a significant decrease in the mean number of INs produced after five days of experimental protocol in one zebra finch. It went from 5.6 INs before the assay to 4.5 INs after only five days.

While the distribution of INs can vary across time, this downward shift in one bird is quite promising. But of course, this needs to be validated further by first improving the performance of the IN detector, and later replicating this result across multiple birds. It would be interesting to study the effect of reduction in INs on the song quality and properties. It’s also important to quantify the recovery to song once the reinforcement has been stopped. Several studies earlier have tried to understand vocal learning by lesioning certain regions of the brain and studying how this recovery is affected.

Another interesting addition to the study would be to use this protocol to reinforce birds to increase their mean number of INs, rather than decrease them, i.e., play white noise if the bird sings less than 4 INs. The motor preparation hypothesis for INs would predict that it should be easier for the birds to increase INs rather than decrease them. It would be interesting to test this using the same birds with sufficient gap between the two tests.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Raghav Rajan for his support and guidance throughout the project. I’m grateful to all the lab members for their support, especially Dr Sonam Chorol for her assistance during the experiments, and Mr Prakash Raut for taking care of the birds. I would also like to thank my friends and batchmates, Divyansh Gupta and Aditya Pujari, for code debugging sessions and discussions. I would like to acknowledge IISER Pune, KVPY and funding sources: IA/S/21/1/505621, CRG/2021/004690, DST/CSRI/2017/163.

Further reading

- Canopoli, Alessandro, Joshua A. Herbst, and Richard H. R. Hahnloser. 2014. “A Higher Sensory Brain Region Is Involved in Reversing Reinforcement-Induced Vocal Changes in a Songbird.” Journal of Neuroscience 34 (20): 7018–26. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0266-14.2014.

- Kalra, Shikha, Vishruta Yawatkar, Logan S James, Jon T Sakata, and Raghav Rajan. 2021. “Introductory Gestures before Songbird Vocal Displays Are Shaped by Learning and Biological Predispositions.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288 (1943): 20202796. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.2796.

- Price, Philip H. 1979. “Developmental Determinants of Structure in Zebra Finch Song.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 93 (2): 260–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077553.

- Rajan, Raghav, and Allison J. Doupe. 2013. “Behavioral and Neural Signatures of Readiness to Initiate a Learned Motor Sequence.” Current Biology 23 (1): 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.040.

- Rao, Divya, Satoshi Kojima, and Raghav Rajan. 2019. “Sensory Feedback Independent Pre-Song Vocalizations Correlate with Time to Song Initiation.” Journal of Experimental Biology 222 (7):jeb199042. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.199042.

- Scharff, C., and F. Nottebohm. 1991. “A Comparative Study of the Behavioral Deficits Following Lesions of Various Parts of the Zebra Finch Song System: Implications for Vocal Learning.” Journal of Neuroscience 11 (9): 2896–2913. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02896.1991.

- Tumer, Evren C., and Michael S. Brainard. 2007. “Performance Variability Enables Adaptive Plasticity of ‘Crystallized’ Adult Birdsong.” Nature 450 (7173): 1240–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06390.

- Veit, Lena, Lucas Y Tian, Christian J Monroy Hernandez, and Michael S Brainard. 2021. “Songbirds Can Learn Flexible Contextual Control over Syllable Sequencing.” ELife 10 (June):e61610. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.61610.