A Balancing Act

Vasudha Kulkarni, Saismit Naik, Aharna Sarkar, Khushi Datri, Shaswat Nair, Srivathsa Kurpad, Sultan Nazir

This article was first published in the 98 Acres (investigative journalism) section of IISER Pune’s college magazine, Kalpa (2022). All figures and images were designed by Vedanth S.V.U.

~~~~~

“If there is a deadline, then I would rush to the lab in the morning. And my entire day would be just to get that finished off. Whatever it takes, whether it takes the entire night. There are many days when I leave the lab in the morning, after working the entire night.”

“There are times when I’m awake for two days straight. And there are times when I don’t have such requirements for my experiments. But even outside the lab, there’s writing or reading going on, that I don’t keep track of how many hours I am spending at work.”

“It was like I would start at 9:30 in the morning. And it can end any time from eight o’clock in the evening to midnight, or sometimes I stay up all night in the lab.”

Labs at IISER never sleep. We love our science, but it seems to come at a price.

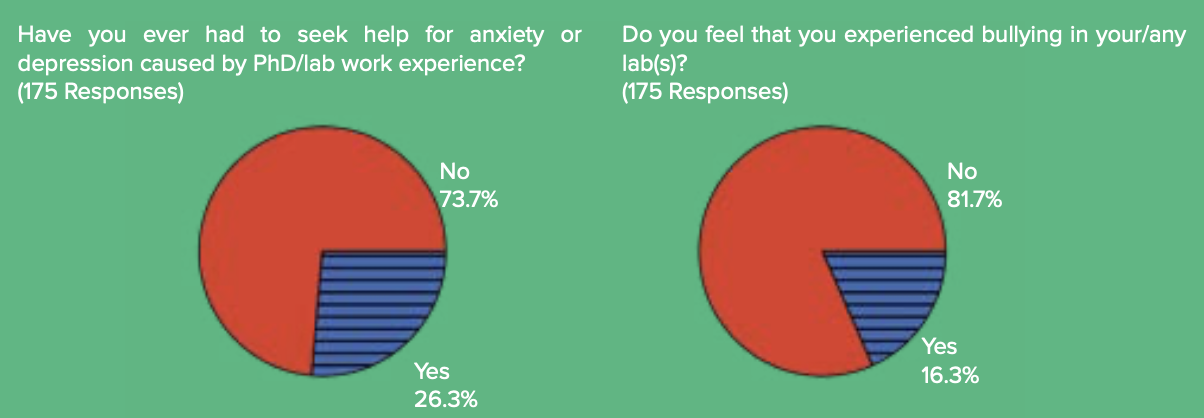

We at 98 Acres set out to learn the work-life balance status on campus, which led us to scrutinise various aspects of the work culture in IISER’s labs. In our survey, we found out that 26% of students have had to seek help for academic stresses, 18% have experienced bullying in labs, and 24% of the students sleep for less than 6 hours a day. The long hours and exacting days are a recurrent theme in the interviews we conducted with PhD scholars of IISER Pune. Studies on a larger scale with international student input have found similar trends, and they mirror our worrying findings. [1, 2, 3]

A PhD degree in any part of the world is stressful. Akanksha, a final-year PhD candidate, told us, “Initially, when I started my PhD, it was very isolating… before we join PhD, we face everything as a group in a classroom setting. [In a PhD] you are the only new person in that setting. You are the only person who’s learning that new technique or who’s learning to navigate through that place or research question itself.” Further, the uncertainty of experiments and irregular stipends combined with the cut-throat competition for high-impact publications and procuring faculty positions are significant factors in deciding the work-life balance of a PhD student. Students end up putting in regular long hours, which fosters a collective workaholic culture in the labs. 30% of our respondents worked in the lab for more than the standard 8 hours a day, and 40-50% of our respondents spent less than an hour every day participating in clubs, spending time with their friends, doing domestic work, and other hobbies. Our interviews reveal a pervasive attitude behind these figures – PhD students overworking themselves is considered conventional, and spending late hours in the lab is lauded, even if it means taking long, frequent coffee breaks. As Vishakha, one of IISER’s counsellors, aptly said: “It’s a cycle. If you’re trying to take a break, the guilt comes in, and then you stop [taking a break]. You must make a lot of conscious effort to break [the cycle].”

PIs and sometimes even lab mates often keep track of the time spent in the lab. Neel*, a senior PhD scholar, told us that their lab mates were judgemental about their participation in extracurricular activities. Every time they left to play with someone, the lab mates would say, “Oh my God, your work is finished?” and attribute any error to Neel’s “tiredness from playing so much.” “If you focus on something other than academics, it’s considered that you’re distracted and don’t have much passion for science,” Neel added. Maneck*, a BS-MS student, who worked in the lab around his class schedule, was berated for not spending enough time in the lab, “Scores don’t matter. What matters is whether you know how to work or not. And clearly, you need more practice in the lab work.” Several interviewees brought up that this attitude varies based on the lab environment and the nature of work. Rashmi, a PhD student in the biology department, put it succinctly, “Everybody is overworking because there is a lot of work.”

Indian academia comes with its unique challenges. It is faced with a harsher scarcity of funds. Students take on lab management roles in places without lab managers or good administrative support. Arun*, a senior PhD scholar, shared their experience – “You are about to start an experiment, and is delayed, you need to follow it up. So, it’s just relentless running from purchase to accounts to back up; it keeps going on and on. So, there’s a lot of non-research activity.” Irregular salaries create a lack of financial security that can be debilitating for those who are expected to support their families. In a 2021 IndiaBioscience article, Joel P. Joseph writes that these problems mainly stem from two factors – variation in stipends and irregularities in disbursal [4, 5a, 5b]. Shaillendra, a PhD scholar in the physics department, told us, “I personally believe that the thing which is more severe is that your stipend gets over and you have not finished yet. In IISER itself, you will find a lot of cases. Because this stipend is only for 5 years [for PhD students], they do not get any economic support.” According to a PhD student’s estimate, more than half the students go beyond their normal tenure to complete their PhD. After an extension of 6 months, students are left searching for other funding sources, without which some take up part-time jobs giving private tuition.

~~~~~

Indian women in PhD programs further experience constant familial pressure to get married. “I think for females, it’s like, every month, every phone call like that you speak to aunt, uncle, or whoever you call, they’re going to ask you that question [about marriage],” shared Dr Keerthi Harikrishnan, a DST Scientist at IISER Pune, shared with us. Though it is not true for all, many female students are expected to get married and prioritise domestic work over their already demanding careers, as reported by another IndiaBioscience 2021 article [6]. On the other hand, misogyny is not unique to the Indian context; it’s pervasive in academia. In a previous investigation by 98 Acres [7], our team reported in detail various instances where casually strewn sexist remarks can create an unequal workplace environment and cripple their confidence. In a conversation with a PhD student, they highlighted an instance when a professor reportedly said, “Why did I hire girls if the lab is going to be messy?”

~~~~~

A PhD is not merely work but a way of life. Dr Harikrishnan elaborates, “Academia is built in such a way it allows a lot of creative freedom to pursue what you want, and that is not bound by typical nine-to-five work hours. You are only bound by the goals that you set for yourself.” This allows for varied work styles, but the hard work is rewarded with the joy of discovery.

The path of a PhD to creating original research expects long work hours, but it also needs guidance. A student’s experience in academia is often heavily decided by the kind of support they receive from their PI. But this creates a unique skew in the hierarchy, where a PhD student’s life is closely dictated by the PI with whom they’re working. Everything from when they start their day – “Many times we’re like woken up by a call from our PI… You wake up to a call an angry call mostly. And then you don’t have time to eat, because you’re in panic mode, because he’s just calling and yelling at you or something. So, you just run out and go to the lab,” – to what they work on – “I have been overburdened with a lot many projects, which are not mine, which are basically second or third author projects and not part of my thesis.” – and even police personal aspects of their life – “I know so many of my friends who had to cancel trips, who had to cancel doctor’s appointments, just because they couldn’t get a leave.” While there are official avenues that PhD students could pursue to seek redressal, no system protects them from the PI refusing to give recommendation letters, which could ground their scientific career before it takes off.

Several PIs control minute details of their students’ projects, giving them little creative freedom. Ashley*, a PhD student at IISER Pune, told us, “They [PIs] treat the PhD students as hands that are doing, you know, who is there to repeat some protocols and to carry out some instructions.” Chaitanya*, another PhD candidate who has been overburdened with work, said, “I cannot be honest to him [the PI] because he is the boss. We can’t disagree with him. At any point, even conceptually, even scientifically, if there are some disagreements, it takes a whole lot of effort and time to explain it to him. It takes a whole lot of convincing that goes [into it], so that he agrees with our point.”

Given the spate of challenges that PhD scholars navigate, if they find themselves unable to work with their PI or in the lab, their options are limited. While integrated PhD students get more exposure to different labs through rotations over three semesters, PhD students have lesser time to decide on their lab, mentor and project. One of the problems in switching labs is the time constraint – when they change labs, they will have only 3-4 years of their PhD tenure left to start a new project, making PIs reluctant to accept students from other labs. Further, there is a stigma attached to the student who wishes to change labs.

Farhan, an ex-student of IISER Pune’s PhD program who successfully switched labs during his PhD tenure, told us that other professors consider that the student must be “fickle-minded” or “lacking focus”. “That’s what I heard people say about me, that you were probably not focused enough… Whereas I knew that that was the hardest I had ever worked,” he said. Even if one manages to change labs, when the PI leaves the institute for instance, the shift can still be quite demanding. Neel* shared with us, “Changing your project completely and then working on it from scratch and the stress [when] you start seeing other students of your batch, actually progressing with the project they started with in the first place. So that stress also adds to the pressure.”

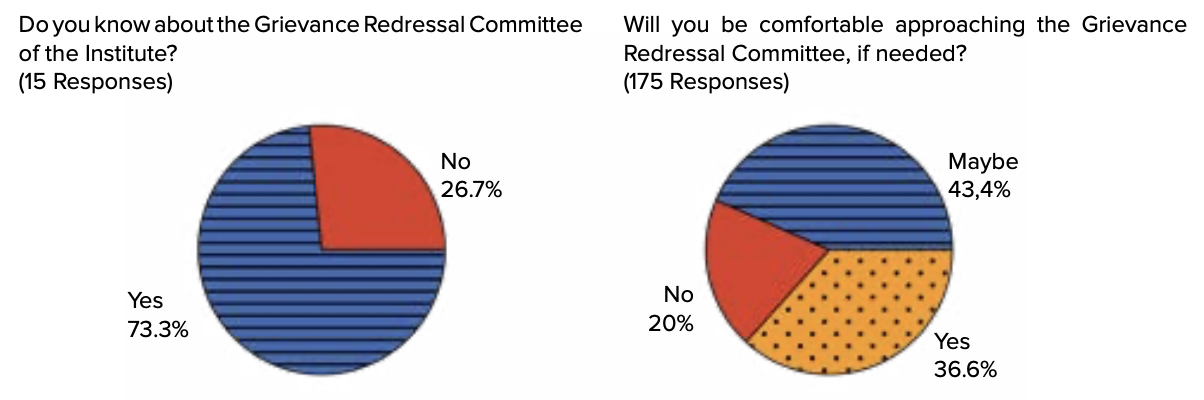

Apart from many more instances of micromanaging, we also learned that extreme management styles could end up controlling students’ lives outside the lab, bullying, name- calling, and shaming. Mechanisms are in place to address such complaints in the form of the Grievance redressal cell (GRC) in the institute, but unfortunately, many students don’t know it exists or fear that they would not get a recommendation letter from the PI. We further wished to get a faculty’s perspective on the subject. Dr Sourabh Dube said, “I also feel that it’s me who should be making the judgment for them, not them because I don’t necessarily think they are at that point they see the repercussions of it [not prioritising work]. Unfortunately, I see how it can be looked at; it can be thought of as ‘you’re forcing them to work’, but yes, I am forcing them to work because that time is important, that time you have to focus on the work. This is not true of, say, the last two years of your PhD when you are very trained, and you know what’s important and what’s not.”

~~~~~

The stresses from the PI, the lab dynamics and the toxic and intense work culture can have severe and long-lasting effects on PhD scholars. A stark effect shows up in our survey – 26% of the PhD candidates were seeking help for anxiety or depression caused by their work. While it is good that there is better awareness and many of them are seeking help from counsellors to deal with their stresses, it is still alarming that such a large fraction faces unmanageable stresses.

Shree Hari, an integrated PhD in the Physics department, has faced the unfortunate repercussions of the flaws in the system. In a previous article in Kalpa [10], he talked about the social isolation and lack of support from different systems in the institute. He returned to the institute last year after his medical leave, but throughout the process of leading up to the leave and after rejoining the institute, the insensitivity or ignorance about depression or other pressures on a PhD student made everything an uphill battle, when simply being a PhD student was hard enough.

He wrote to us, “While statistics such as percentage of PhD students suffering from mental health elucidate much about the broken system, it also hides, in a sense, the stories and pain of each of those individuals who are living through the broken system. When I was sick, the first thought on opening my eyes every morning was of contempt. Contempt for myself.Contempt that I couldn’t kill myself or die in the night to not wake up today. How many healthy, functioning adults think that, every morning? Do you think that every morning? How many jobs have a quarter of its working population go through some version of this thought? I fortunately never took that path. Killing oneself requires going against self-preservation instinct, something life has nurtured for a billion years, and some students still have to choose that option. That is the amount of pain and suffering inflicted on students. That is the reality one must accept when reading these numbers.” Insidious effects of the power asymmetry in labs have come to the open through reportings of extreme cases at elite institutes such as the NCBS retraction case in June 2021 [8] and the frighteningly high number of suicide cases in IISc and IISERs [9], which was heightened by the pandemic and brought into the glare yet again by the unfortunate demise of a senior PhD scholar at IISER Kolkata in April 2022.

~~~~~

Systemic issues are multi-faceted and are complicated to root out entirely, but we wished to understand how they could be made better. When we interviewed several PhD scholars about their experiences, we also asked them for feedback on how the system could be improved to make life better for them. One of the most common responses we got from them was to institute an anonymous feedback system so that PhD candidates could provide feedback and share their concerns without fearing retaliation. The feedback from the lab members should also reflect in the PI’s career, as one of the axes of a successful academic career involves good mentoring.

Some students were concerned that the PI might be able to discern the person behind anonymous criticisms. So, another prevalent idea was to have a non-academic mentor for every PhD student, who is from a different department, or a different field. Apoorva* , a senior PhD scholar, shared with us, “I have thought about approaching someone when I have issues with my PI… [but] all the people that I’m supposed to talk to are, at the end of the day, friends with my PI and they’ll probably side with him rather than me.” As we learned through our interviews, the fear of breach of anonymity extends to using campus counselling services because many students believe the channels are porous. It makes the large figure of 26% of PhD students who have accessed mental health services a conservative estimate for the number of students who need it.

Another important suggestion was to limit overworking by PhD students. Akanksha, a senior PhD scholar in the Biology department, elucidated very well, “Many professions which require high skills and brainpower, they have systems in place where a doctor can perform only so many surgeries a week, or a pilot can fly only so many hours at a stretch. If a PhD student is working too many hours in a week, then they’re supposed to take a break so that they can come back and work better. But academia as such does not have a system, even for PIs, to detect or regulate working hours when a PhD student comes in the morning after having worked all night long.” Overworking is also a safety hazard, especially when PhD students work with dangerous chemicals. Closing the labs in the evening is not feasible and recording the time PhD students spend in the lab might overstep into surveillance. Akanksha suggested that institutes should set up an HR department for PhD scholars, which can anonymously regulate working hours and act as a support structure to help with other concerns they might have.

An immediately applicable suggestion is to conduct orientations and workshops on lab safety, sexual harassment, mental health, bullying and ragging, ethics and grievance redressal to all students and professors every year and require mandatory attendance from everyone. Along similar lines, some PhD candidates also suggested training for interested graduate students in administrative roles and teaching. Several PhD students also suggested that PIs should also have workshops on mentoring, management and professional conduct.

We also spoke to several department chairs at IISER Pune, all of whom listened and responded to the suggestions by PhD scholars. There is an institute-level Internal Committee and an Ethics Committee, which take care of harassment and research ethics cases, respectively, and departmental Student Well-Being Committees to redress students’ concerns and facilitate lab changes. Regular orientations and reminders of these facilities would increase their accessibility. In the math department, PhD students take classes for the first one and a half years, so they have a longer period to get to know PIs and choose their mentors. This is not feasible in all departments because students often come in with specific interests. But there should be a longer rotation period and the chance to switch labs for students who wish to do so. IISER Pune is also establishing a department of science education that will offer teacher training courses for interested early career researchers and graduate students.

Dr Thomas Pucadyil, the Chair of the Biology Department, also told us that the Department is thinking of setting up “a portal for students to anonymously send in any concerns they may have with regards to research ethics. For this, we are in the process of setting up a committee, and this committee is going to be different; it’s going to be composed of senior and experienced faculty members who are affiliated with the department in a visiting/emeritus capacity.”

All in all, we are part of a unique system that provides a platform to ask interesting questions and come up with creative ways to satiate our curiosity. Scientific knowledge accrues through the collaborative and cumulative effort of students, scientists and professors over time. But in its current hierarchical structure, it’s also plagued by systemic issues that disproportionately affect graduate students. The research community will have much to gain with a safer and healthier work environment for its graduate students who work tirelessly to extend the boundary of our current knowledge.

~~~~~

References

- Graduate survey (Nature 2017)

- Obstacles for LBTQ+ scientists (Nature 2019)

- CACTUS Foundation mental health survey

- A multimedia report on funding delays

- Two references -

a. Money and Mental health

b. Broken promise of Indian Science - Society, career and the female scientist

- Misogyny Inc. (Kalpa 2020, pg 14-21)

- TIFR probe NCBS Arati Ramesh retraction case

- 4 suicides in 7 months at IISc Banaglore

- The Year that Wasn’t by Shree Hari Mittal (Kalpa 2021, pg 64-65)

- Interesting article on whether academia is for everyone and how to transition from academia: Beyond Academic stress and burnout